So I've finally decided to jump off the cliff and write a novel.

That sentence will have one of many reactions, depending on the person:

1) The most common reaction: absolutely nothing, because most people won't read this blog post so they won't be aware of this momentous (for me) decision.

2) A modest shrug of approval to themselves followed up by the immediate forgetting that this is taking place.

3) "Why the hell are you telling us about this?" said to self, and sometimes coupled with the thought of "instead of actually just writing the damned thing."

4) Encouragement and support by well-meaning, kind-hearted people who will probably forget about it immediately upon reading this post or seeing this headline on the many social media venues where this will appear. This person's reaction will be along the lines of, "Oh, that's great. I'm sure he'll tell us about it when it's done."

5) And the least common reaction from people: a barrage of questions not limited to, but including, the following: "What's it going to be about?", "When will it be finished?", "How long is it going to be?", "It's going to take you HOW long?", "I think you should write a book about..."

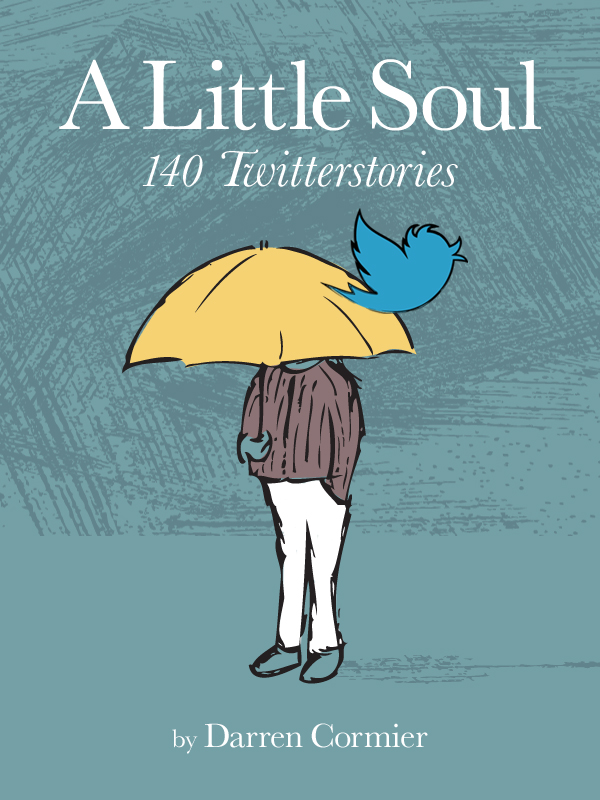

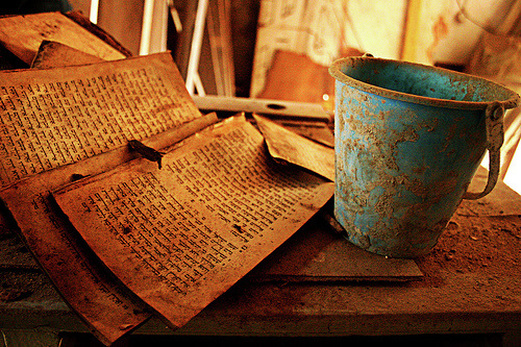

But, yes, I have decided to write a novel. For those who know me, this is a huge deal. The idea of writing a novel scares the living hell out of me. I am not what most would call attention sufficient. (It has taken me about an hour and a half to write this far due to various distractions which, were I to list them, would make this post longer than our tax code.) I've always written short stories and over the years have focused more and more on shorter structures, perhaps due to the aforementioned lack of attention sufficiency.On top of the usual doubts that accompany the process of writing, I have decided this will be historical fiction. Which just increases the amount of doubts to a near crippling level: Do you conduct the research first and then start writing? Or do I start writing and then conduct research to fill in those details I am unsure of? Which voice/character starts the story? How much research is too much research? (And when will I be conducting research as a means of procrastination, instead of just writing the damned thing?); what if, after 200 pages, you realize you need to rewrite the entire book or the scene on page 250 is actually how you need to open the book, thus forcing you to rearrange the entire structure; or you realize you need to change the point of view from third to first person? With a short story, these issues are easier to handle: thirty pages is much more manageable to rearrange and cannibalize than three to four hundred."Why would you do this if you know it's going to cause this much torment?" Good question, hypothetical reader. Over the past few years I have jumped off many proverbial cliffs in terms of pursuing life goals that for various reasons--none of which were any good--I decided to avoid for years and years and years and... well, you get the point. Since I was in the process of tearing down my own self-constructed scaffolding, I figured I would just jump at the next obstacle, the next goal, and deal with the fear and prospect of failure later. That was writing this book, the idea for which has been bouncing around my head for almost six years now.

So for the next few years be prepared to be bombarded with blog entries about historical research, the frustrations of writing, and Cambodia. And the occasional writing-induced outburst.

As always, thank you.

Warning: this post might not be uplifting. But I hope it is thought-provoking and moving. I have been reading Georges Perec's W, or The Memory of Childhood. I'm almost finished. The book alternates between Perec trying to recall his childhood, and the description of a mythical island off Tierra del Fuego called W, where the pursuit of the Olympic ideal is the sole purpose of existence, athletic competition the only occupation, where victory is praised and feted but fleeting, and those who did not prevail are mocked and punished, even if they are previous victors. (Perec's childhood was during the Nazi invasion and occupation of France; the story of the island of W is an allegory of those atrocities.) Perec's father passed away when he was very young--and, a few years after, his mother put him on a train in order to save him from capture. He later discovered that his mother died on a train en rote to Auschwitz shortly thereafter. He was raised by his father's sister and her husband. At one point he addresses his personal need to write in relation to the events of his childhood, his lack of memories of his parents, and how his writing life might be intertwined with his own search for emotions about his parents:"I do not know whether I have anything to say, I know that I am saying nothing; I do not know if what I might have to say is unsaid because it is unsayable (the unsayable is not buried inside writing, it is what prompted it in the first place); I know that what I say is blank, is neutral, is a sign, once and for all, of a once-and-for-all annihilation.That is what I am saying, that is what I am writing, and that's all there is in the words I trace and in the lines the words make and in the blanks that the gaps between the lines create: it would be quite pointless to hunt down my slips (for instance, I wrote "I committed" instead of "I made", a propos of my mistakes in copying down my mother's name), or to muse for hours on the length of my father's capote... for all I shall ever find in my very reiteration is the final refraction of a voice that is absent from writing, the scandal of their silence and of mine. I am not writing in order to say that I shall say nothing, I am not writing to say that I have nothing to say. I write: I write because we lived together, because I was one amongst them, a shadow amongst their shadows, a body close to their bodies. I write because they left in me their indelible mark, whose trace is writing. Their memory is dead in writing; writing is the memory of their death and the assertion of my life."I read that section and I think of myself, and I think of all my writer friends and all my writer non-friends (writers I don't know personally). Not because we share the same background or childhood as Perec--we don't, even those who lost their parents at a young age don't share his background--but because that is why we write: to express our emotions, or to be able to express our lack of emotions, to be able to understand our own convoluted and self-absorbed search for ourselves, for our emotional connection to the world. We write to keep alive that part of us we don't show others, that part of us we wish to keep alive that isn't anymore, to keep alive other people. I write to keep alive the memory of my grandfather, the memories that others have of him, of him slipping quarters into my brother's jacket as they walked down the beach, my brother, upon finding them, believing he had a magical jacket. I write to keep alive my own memories of my grandfather's and our many, multi-layered handshakes: the lumberjack, milking the cow, rowing the boat, and the customary, American handshake, among others; I write to keep alive the memory of my grandmother washing dishes in pearls and a dress, of eating an entire 2 pound box of Froot Loops in one sitting as a snack (she and I did this); and, lastly, I now write as a means to keep alive the memory of my own father, of Bowling for People, which consisted of rolling rubber balls at a ten-pin set up of Weebles (they wobble but they don't fall down), of cursing at hockey referees, of installing sliding windows until nine o'clock on a hot, summer night, of midnight bowls of cereal watching MST3K. Steve Almond wrote that we write "to arouse the anguish hidden inside us, the bad news of our hearts." I would also say we do it to keep alive the memories of those who have formed us, for, unwittingly or not, they helped create this compulsion to share those parts of us we ourselves don't understand; they helped to form this compulsion to write.

Anthony Trollope wrote seven pages a day, seven days a week. And would actually begin a new book if he came to the end of one before his day’s quota had been met. – David Markson, This is Not a Novel Mood affects everything we do, how we interact with other people, affects our productivity at work, affects how personal relationships, our energy levels. When we are in a sour mood (angry, sad, depressed, frustrated, etc.) our productivity at work suffers, we don't feel like working or interacting with other people, others' good moods will aggravate us, seeing tiny little moments of joy from others will annoy us and make us wish that person would leave. We probably don't want to create music, art, literature, cook, etc. Likewise when we are in a happy mood, when we are excited, content, we are more prone to creativity, our productivity increases, our interactions with others is more affable, tiny instances that will usually aggravate us (the copier being out of ribbon, the cat knocking over our glass of water, the next door neighbor mowing his lawn at 8p when we're trying to enjoy a book or our favorite TV show) we can shrug off. But how does mood affect writing, or any art for that matter, assuming of course that we have mustered up the courage to write in the first place, that we have been able to see past our elation and attention devouring ecstasy, past our lethargy and depression to focus on writing? One wonders if Anthony Trollope had this problem. As shown in the Markson quote above, Trollope clearly did not have a problem in garnering the motivation to write. However, what was his output like on those days he did not feel quite so creative, on those days he just didn't feel enthusiastic about the writing process, those days when he would have rather just stayed in bed with a bottle of wine and asked his servants to bring him a ham sandwich, he was not getting out of his sleeping gown? Was his output more dour, did he decide to work on stories or scenes that would reflect his mood? If he woke up in a foul mood one morning, but if in the novel he was working on at that moment he was presently working on a blissful wedding scene, would he have been able to push aside his own negativity and create the scene the novel demanded? Or did his mood alter the scene? Would he have to go back and revise what he had initially written as a crashed wedding, a blasphemous affair into something more mood appropriate? And vice versa. If one is in an elated mood, are they more capable of accessing the dark recesses of their mind, of their heart, if they are working on a murder scene or a scene of heartbreak, or emotional turmoil? Does the act of writing itself allow us to focus not on ourselves but on the work? Is the outlet enough to allow us to compartmentalize our private lives from our writing lives? Or does our personal mood affect the output of what we write? A writer friend wrote a while ago that when she is in the midst of writing an emotional scene in her book or her story that she can't help but become emotional as well, that what the characters are going through affect her. After completing the scene, she feels emotionally drained. And perhaps this is a symbiotic nature of the work itself. I haven't asked her, but I'm assuming she went into her writing that day knowing that the piece would be emotional, but that earlier she was probably in a good mood. As she began writing the events themselves began to affect her, her writing, the scene affecting her mood, her mood reflecting in her writing, scene and personal disposition mirroring each other, fiction reflecting life reflecting fiction reflecting life reflecting.... I cannot say this has happened before. In one of my stories (as yet unpublished) I wrote the scene of a young man watching the death of his mother, the two of them sharing a cigarette in the kitchen after she collapsed while they waited for the ambulance. At the risk of sounding immodest, it is a very powerful scene. However, when I was writing it, I only felt pleasure that I was able to capture an emotionally wrenching scene with such authenticity. The writing did not leave me emotional for my character; I did not feel saddened afterward, nor was my mood being reflected in the story itself. However, I did know the night before that I would need to be a bit more alert to write the scene. Once I arrived at the point of the mother's death flashback, it was 3am, and my eyes were sagging to the floor. I realized I would need to be of full alertness to properly convey the emotional intensity of the scene. But during the writing of it, I felt nothing but placidity, an unwavering equanimity. What my character was going through did not affect my mood. Or did it? Would I have been able to write so authentically as my character had I lost my job earlier in the day? Would I have been able to render the devastating power conveyed by the shared cigarette had I won the lottery earlier that afternoon? (Would I even have been writing if I had won the lottery earlier that afternoon?) It's possible that my mood of calmness was portrayed in the calm manner by which I wrote. We can never be sure. Eric Maisel wrote in his book Deep Writing about how to best access our deep feelings, how to allow ourselves to become free of our inhibitions and fears through writing about them, how writing can be a form of therapy. He wrote of how our own years-long issues can be a catalyst for our stories and be re-explored through story. At the beginning of the book he quoted a former patient who believed that a healthy sense of self and well-being was needed to create art: When I am completely healthy, completely healed, will there be more art in me? I think there will be and maybe it will be some of the best. That sense of wholeness and well-being must be a wonderful place to make art from. I hope I get a chance to be there, even if only for a while.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed